From the Beach Boys to AI Tools: Mark Linett’s Journey Through Music Engineering

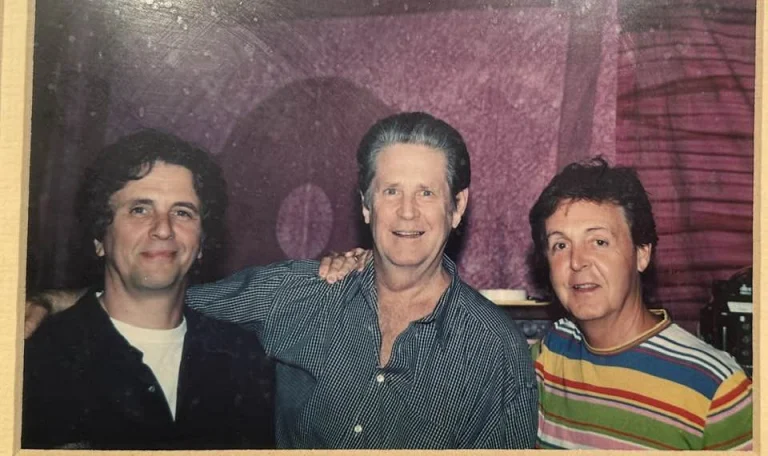

American record producer and audio engineer, Mark Linett, is a studio veteran. Entering studio life in the 1970s on analogue recording boards, Linett has expertly navigated the evolving technological landscape of music production. The Grammy award winner is best known for his remixing and remastering of the Beach Boys’ catalogue and has also worked with scores of notable artists such as Brian Wilson, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Jane’s Addiction, Randy Newman and many others.

Growing up in New York during the 1960s, Linett dabbled in stage lighting and even ran a light show company as a teenager. His love for music and recording, influenced by his father’s interest in hi-fi audio, led him to start a PA company right out of high school, organising and managing small concerts. Despite youthful enthusiasm, Mark and his partners struggled due to limited resources and knowledge and, realising his true passion was recording, he moved to California and worked at a modest studio, using the space to experiment and hone his skills.

After several years of working at low-level studios with little progress, he returned to New York, and reluctantly went back to college, which is where Mark picks up the story…

How did you manage to stay connected to the music industry while pursuing your studies at Boston University?

While I was going to Boston University I still wanted to be in the business. There were only really two or three studios in Boston but I was knocking on doors and I met Joe Ciccarelli who at the time was a second engineer. I also went out to Hanley Sound, who were one of the inventors of real good concert sound. They didn’t have anything for me, but I met somebody there who, a short time later, called to tell me that Frank Zappa was starting a tour that night in New Haven and the mixer who Hanley Sound had supplied for the tour was deathly ill and wasn’t going to be able to do the job. I called the road manager, got a little prop plane down to New Haven and arrived just after the opening act, which was Mountain. The road manager told me to go out to front of house and watch what the guy was doing because I would be taking over after that night. In fact, I took over after about 15 minutes as the guy was so unwell.

I did the show and I packed up the gear, then the road manager came out said, “here’s the deal. The pay is 400 a week, 25 a day per DM. If you get caught using drugs, you’re fired.” So, the next morning I find myself on the tour bus with Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart and the crew and ironically, our next stop was The Capitol Theater in Passaic, New Jersey, which was where my PA company went down the drain four or five years before then. I’d just turned 23 years old.

Frank was great. The band was great. Frank was forward thinking – he was one of the first guys to own his own PA and lights rather than have the promoter rent them. After we finished that tour, they made a deal to rent the production, the PA lights and Frank’s crew to run it, to go out on tour with the Electric Light Orchestra.

Later, the road manager and I went to work for Caballo Ruffalo and he got me the job mixing for Earth, Wind and Fire. A great band but it wasn’t a great gig. The people were nice but the PA was not up to the task. I was still tasked with being the PA chief and mixing and we were playing stadiums and arenas and it was brutal, it almost killed me. I suddenly started to feel like this wasn’t the life I wanted, I didn’t want to be a road dog, but I still needed an income.

I had met George Massenburg working for Earth, Wind and Fire. He was a recording engineer and I had done some second engineering for him. He did a lot of work at Sunset Sound here in LA and in those days those kinds of studios usually had two assistant engineers for every studio because they tended to work dual shifts. They were opening a new Studio Three and George helped me get the job. I spent around a year and a half on staff there and then went independent, which was not easy and wasn’t really working out so well. I was then told about a job that had opened at the Warner Brothers record studio called Amigo. I went out there, did an interview and they hired me. I was there for the next 2-3 years until they closed the place, and I worked on a lot of Ricky Lee Jones records, Los Lobos, Michael McDonald, and a bunch more.

Then I went indie, but by then I had a client base, so it was okay. One day, I called what was then Oceanway Studios, which had been the United Western Complex where the Beach Boys were filming and recording, to book some time for a project. At the end of the call, the woman I was speaking to said, by the way, we’ve got a last-minute session on Thursday for Brian Wilson. We need an engineer, do you want to do it? I worked on that project for a year and a half and that led to seven, eight or nine Brian Wilson albums, and that also led to my involvement in all the archive projects for the Beach Boys.

I suddenly started to feel like this wasn’t the life I wanted, I didn’t want to be a road dog, but I still needed an income.

Let's talk about those archives, what were your main challenges?

The first job I was given was Pet Sounds [The Beach Boys] on CD. This is when CD was starting and after that, I was given the task of putting the whole Capitol catalog on CD. The next thing was a box set called Good Vibrations. It was a 5 CD box set tracing the Beach Boys’ entire career with outtakes, bonus tracks, all kinds of stuff like that. Then somebody got the idea of doing a big box set of the Pet Sounds album and I did the first true stereo mix of that. It had never been done in anything but Duophonic up to that point, largely because of the way things were recorded in the ‘60s. Then, in around ’66 or ’67, bands or artists started being interested in doing stereo records, but if you came from the era of AM radio and pop records and 45 RPM singles, it was mono all the way.

Your typical recording would be that you had the track in mono but then you’d bounce that to another machine and just keep doing that until you had everything you wanted and then mixed it to mono. The Beach Boys records were like that. Brian let the engineers spread the basic track out and do four tracks and then we’d mix that to mono onto one track of a four track, or he took it over to CBS Recording that had the first eight track in LA, bounce it over there and then he would have seven tracks to do vocals.

So, the problem for doing a real stereo mix was that what you wound up with at the end was a mono track on the master tape, and whatever number of vocals. So, the question was, how do we sync all these different tapes up and it really wasn’t something you could do until digital recording came and by the time I did it, we had Sony Dash machines.

So, to do that record, I had to transfer the three-track backing track (I was using a 48 track Sony) then manually sync the overdub reels by playing with the varispeed speed and manually dropping it in using the mono track as a guide and try to get that phasing with the three track combine. When I got it close enough, so it would phase for 20 or 30 seconds, I would dump the whole thing over and then I would move the vocals (because you’ve got drift) using those two band tracks, then keep moving the vocals to keep the band in phasing and wind up with a master that had somewhere between eight and twelve tracks that I could then mix from.

I did it again 3-4 years later when we did a 5.1 mix, but by then we had DAWs (I used Nuendo for that one). Now we have Time Shift, I can sync up a bunch of tapes in half an hour, it’s the easiest thing in the world to do that.

I’ve been using various AI extraction programs a lot recently to deconstruct the originals. Right now, I could deconstruct a mono band track or the component parts of a three track recording and I’ve got more stuff I can move around. It becomes really useful for things like mixes of The Beach Boys stuff, which I’ve done recently, because you’re trying to do something in 12 speakers. So, if I’ve got a mono backing track, you have the bass in the centre and the drums here… a little bit of spread makes a big difference rather than still dealing with the question of ‘where do I put this mono track’? It’s not too bad in stereo, but in surround it gets tricky.

So how did Chameleon come to help you in more recent years?

I have samples of pretty much every chamber in town, I started running them in Altiverb a number of years ago, but I never really had a Gold Star Studios sample. That was the first thing I tried – I could run any of the recordings through Chameleon and out would come an IR. Just yesterday I got a tape that had a printed stereo chamber at Gold Star, so I ran that through Chameleon (just the chamber), and it seems like it’s the best created IR so far from those recordings.

I could run any of the recordings through Chameleon and out would come an IR!

Some people don’t quite understand that you can put an entire musical track through Chameleon and it figures out which bit is the reverb and creates the IR. Did it feel like voodoo when you first used it?

Yeah, because it could hear the reverb and instantly give you an IR for it, and its companion deverb. I had a big use for that a couple of weeks ago because I’m remastering a Ricky Lee Jones album from ‘82 or ‘83 called Girl At Her Volcano and there’s a bonus track on there that was a cassette recording from Europe. It was not well-recorded, there was lots of hum, and at the time it was only put on the cassette of the album not the vinyl so I was piling up three or four URI 565 notch filters to try and get the hum out. Now, of course, there’s all kinds of restoration tools for that. I did an AI split of the extraction of the whole thing, just piano and voice, but there was a lot of reverb on the voice. I could now mix the balanced piano and vocal, but I still had a lot of reverb so I used the deverb – it wouldn’t work to take all the reverb out and then add some back in – so took it down to about 20% and it made it much better. All this stuff is just getting amazing!

You were at the start of a lot of this stuff – you've earned your stripes on analogue boards, and then you've moved into the world of DAWs, and now we're in the world of AI and track. It seems you've found it relatively easy to keep adapting as technology has, would you agree?

My attitude is similar to a lot of people. I would never want to go back to tape or, more importantly, big format consoles, and not mixing in the box. It’s certainly a little bit of laziness and a certain amount of market reaction in the sense that it’s now expected that if you do a mix and the producer or the artist says, ‘I like it, but get the tambourine out here’, or, ‘turn it down’, and you can do that in 15 minutes. So that’s a convenience because it used to take half a day to recall a mix and it was never the same anyway.

But mostly, it’s because it allows for creativity in ways that were all but impossible. We’re in the digital age and mixing in the box there’s so many things that you can do – sub buses and side chains and, so forth that would be impossible on an analog console. But, above all, you can just put up a session and just mix. You don’t have to get hung up on the technology, or the method, you can just use the creative part of your brain.

As the music industry continues to evolve, there’s no doubt that Mark Linett will continue to embrace new technologies while maintaining his passion for innovation and creativity. His fluidity and unwavering commitment to high-quality sound have made him a trusted name in both analogue and digital production throughout his impressive 50-year career and his influence on the industry is sure to resonate for years to come.

We're in the digital age – you don't have to get hung up on the technology or the method, you can just use the creative part of your brain.